The People Problem: Local employers talk challenges and strategy

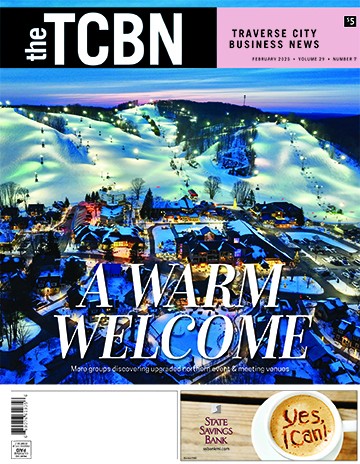

February 2024

Walk down the main drag in any local community and talk with small business owners. Call up the leaders of some of the region’s largest employers. Head over to the kitchen or dining room of virtually any restaurant, anywhere.

Everybody’s talking about one thing: Staffing.

There is without question no hotter topic with businesses of all shapes and sizes these days than the need for employees. For many companies and organizations, the workers who left during and after the COVID-19 pandemic simply haven’t returned, and it’s leading to substantial problems.

Some outfits with years of stability are now scrounging to find the bare minimum to even remain in business. Others are in much better shape, but very few can say with confidence that they’re fully comfortable with their staffing levels. The question is…why?

The TCBN recently formed a roundtable with human resources professionals and other business leaders to discuss this issue and figure out where we are and where we’re going from here. While many positions are going remote, we focused our discussion on positions that require a physical presence at the place of employment.

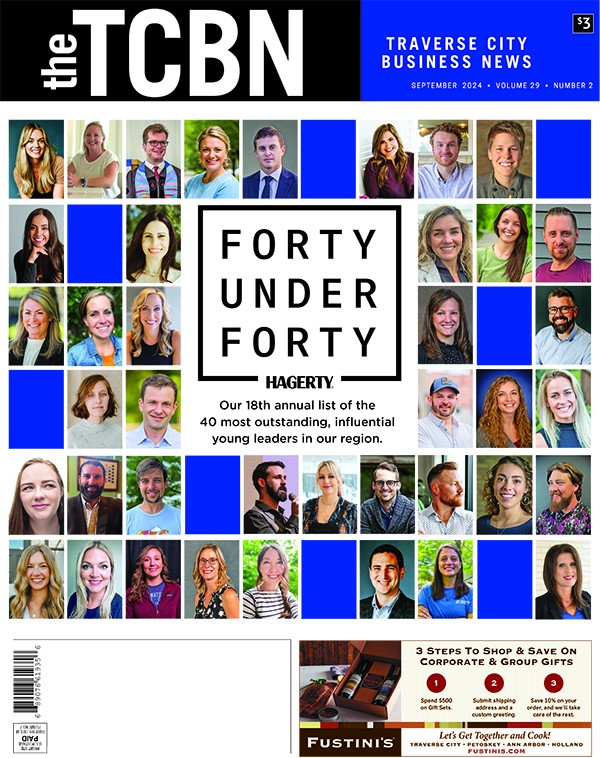

Roundtable participants:

Rob Hanel, Director of People and Space at TentCraft and President of the Traverse Area Human Resource Association

Tifini McClyde-Blythe, Associate Vice President of Human Resources at Interlochen Center for the Arts

Gina Stein, Manager of Talent Acquisition Operations at Munson Healthcare

Coni Taylor, Associate Superintendent for Labor Relations and Legal Services at TCAPS

Jim DeMarsh, Area Manager for the northern unit of Mission Restaurant Group (North Peak, Blue Tractor, etc.)

Tim Norman, General Manager of Grand Traverse Resort & Spa

Seated: Stein, Taylor, DeMarsh; standing: McClyde-Blythe, Norman, Hanel. Photo courtesy of Madi Taylor

Seated: Stein, Taylor, DeMarsh; standing: McClyde-Blythe, Norman, Hanel. Photo courtesy of Madi TaylorFirst things first

It should surprise precisely no one that housing and childcare are the first things mentioned when these professionals are asked about the challenges of hiring and retaining staff.

These issues have been near or at the top of the list for many years prior to COVID, but a tremendous surge in housing prices combined with record low inventory/availability has brought that problem to a boiling point. This issue looms the largest for positions in which there is a limited local talent pool.

“Depending on the starting wage, it’s getting more difficult for someone relocating to our area,” said Gina Stein, manager of talent acquisition operations for Munson Healthcare. “It’s a big barrier.”

Jim DeMarsh, area manager for the northern unit of Mission Restaurant Group, says that housing is "totally unaffordable" for staff in his industry.

“It’s one of the biggest issues, if not the biggest issue,” he said.

The housing crunch often leads to candidates being discouraged from applying for (or even backing out of) jobs that they might really want, but can’t make work.

“We’ve had teachers accept jobs, come up for a weekend to find housing, and then turn around and say ‘Sorry, I can’t accept the position,'” said Coni Taylor, the associate superintendent for labor relations and legal services at TCAPS.

It’s not just a problem for those trying to relocate. Workers who already live here also are getting priced out.

“I've had people that had to leave and go to Cadillac because it was somewhere that they could afford to live, and then consequently couldn’t make the commute from there to Traverse,” DeMarsh said. “There’s a lot of people we employ who don’t have licenses or cars for one reason or another, so proximity is huge.”

Photo courtesy of Madi Taylor

Photo courtesy of Madi TaylorA big difference between now and a few years ago is that housing (and other) costs have skyrocketed while wages have increased, but not by enough to keep up.

“The $17-$20 an hour employee, which I have a ton of, simply cannot afford an apartment with all the other expenses they’re going to have up here,” said Tim Norman, general manager of the Grand Traverse Resort & Spa. “We can’t recruit…because nobody’s going to get in a car and drive up here when they can pay less to live downstate. You cannot get them here.”

Norman and others said this issue is not isolated to entry level or low-paying jobs. Other factors are at play, including mortgage interest rates that have more than doubled after record lows.

“Even if you’re looking at people at the executive level, it just might not make sense for them,” he said. “If I’m trying to recruit someone and they’re going from 2.5% to 6.5 or even 8%, they’re going to look at that and think really hard before they move.”

The lack of (and cost) of childcare is a huge problem, all attendees said. The issue is exacerbated by childcare providers themselves struggling to find bodies, creating a vicious cycle with no end in sight. As with housing, this leads to potential employees turning down or leaving jobs under childcare-induced duress.

“I’ve heard people say that by the time they pay childcare expenses, they’re working for nothing, so they might as well stay home and raise their own children,” Taylor said. “And we would love to offer more extended day childcare options for our staff and for our families, but we can’t staff it. We have the postings up constantly.”

It’s a problem impacting all industries, but arguably hits service industry workers hardest.

“It comes down to someone saying ‘Do I pick up this shift to make X amount of dollars while I pay someone to watch my child, or do I just stay at home?’” DeMarsh said.

Photo courtesy of Madi Taylor

Photo courtesy of Madi TaylorThe region’s relative lack of diversity was also listed as a challenge for attracting out-of-area talent, along with other companies offering remote work that siphons bodies away from local employers. Then there’s the fact that most local employers are competing against other employers for the same talent pool for non-specialized positions. And while this isn’t a current challenge, many local industries are bracing for the impending wave of Baby Boomer retirements, especially with professional staff.

“We have a large number of staff members who are eligible for retirement,” Taylor said. “So there's this huge concern of when is that bubble going to burst, and when those folks leave, how will we go about replacing them?”

Last, nearly everyone at the table said they’ve seen a generational shift in which young people, for one reason or another, are not working as prolifically as they did in years past. This is likely a large factor in the overall dearth of available workers, particularly for hospitality and other related industries.

“That younger demographic, which is a big, big portion of our staff, are not being encouraged by their parents to get out and get that first job,” DeMarsh said. “It used to be that every spring all the kids would come in and you could sift through and pick out who you want, but … I’m just not seeing the young people as much as I used to.”

Just pay them more…right?

If housing and childcare aren’t affordable, it would seem the simple solution is to increase wages. Employers say they’re actually doing so on a relatively drastic level, but there are limits to how high they can go. That’s in large part because their expenses across the board have ballooned in the past few years.

“All of us in business, our margins at the bottom line have shrunk…We're paying so much more, not just in payroll, but also in benefits and insurance,” Norman said. “That's the hidden one nobody wants to talk about. If you go around the room, all our insurance costs have gone up astronomically in the past few years.”

And it’s more than payroll and benefits.

“We recently did an exercise where I asked my managers to go through and look at how the cost of everything they buy has changed over five years,” Norman said. “They’re spending 30, 40, and in some cases 50% more for supplies.”

And there are other factors that lead to squeamishness when it comes to continued raises. Rob Hanel, president of people and space at TentCraft and president of the Traverse Area Human Resource Association, said employers need to walk a fine line in that regard.

“We have to be really careful about what we do, because we’re setting a precedent, and you can’t go backwards,” he said. “These manufacturing jobs in Traverse City that were in that $12 to $15 range are now in the $15 to $20 range, and then next year they're going to be $20 to $25, and we have to think very carefully about whether or not we can keep (it up) when or if the market softens.”

Then there’s the matter of the inflexibility that certain employers face, either due to their funding or their inability to work one-on-one with individual employees due to union or other restrictions.

“We’re funded by taxpayer dollars, and more than 80% of our revenue already goes out to personnel expenditures. So there's not a lot of additional wiggle room,” Taylor said. “I've worked in multiple districts, and we have some of the best teachers I've ever worked with. If I had it, I'd love to give it to them, but it’s just not there.”

Some employers are starting to give their employees what’s known as a total compensation statement, which breaks down an employee’s benefits and perks in monetary terms. An employee who is nominally making $50,000, for instance, can easily see that they’re getting more than $60,000-80,000 once retirement benefits, health insurance and other items are included.

And while that health care contribution isn’t going to help an employee afford a house, it still might prevent them from chasing another job that pays a few more dollars on the front end.

“I’ve had people say to me, ‘Wow, I’m making that much? I’m kind of surprised,'” said Tifini McClyde-Blythe, associate vice president of human resources at Interlochen Center for the Arts. “Communication is critical. We’re investing in a lot of things, and they need to understand what that investment is.”

Give and take

Because it’s been hard to get and keep workers, area employers are also giving a lot of thought to their relationship with workers in terms of pay, flexibility and more. But with this discussion comes certain uncomfortable truths about the current balance of power between employers and employees, particularly in terms of expectations and employee morale in the long run.

Photo courtesy of Madi Taylor

Photo courtesy of Madi TaylorEmployers are in many instances so desperate for bodies that they’ll take anyone they can get – “feel for a pulse and give it a shot,” as DeMarsh put it – but this has led to problems with long-term, quality employees who are rankled by their employers’ duress-based tolerance.

“We have to uphold our standards, and it’s been very, very difficult in the last few years to do that, in terms of what’s acceptable and what isn’t,” DeMarsh said. “But you have to look at the emotional cost for your steadfast employees, and make sure they see us acting in a way that doesn’t reward people who don’t want to show up, or don’t want to work when they do.”

Taylor agrees that there is a growing morale problem.

“There’s just a lot more grace provided because we can’t afford to lose folks,” Taylor added. “And that’s really hard when people who are coming in every day and giving it their all are seeing folks getting away with more than they have would have in the past – it’s a big morale issue.”

There are other big disconnects in regard to advancement and worker value. Norman and others said they’ve noticed a trend of unsustainable or unreasonable expectations from some employees and potential hires in the wake of COVID.

The growing push for more money, for one, can be troubling when the employee is not adding any more value and an employer is increasingly pinched by increased costs across the board.

“They have this built-in mentality coming out of COVID that this is my minimum value, you’ve got to at least get me to here…but now they’re getting 30% more than they were a few years ago, and they haven’t done anything different,” Norman said. “We’re paying more but we’re not getting any more skillset.”

What’s more, employers are increasingly gun shy about pulling the trigger on more pay in what has become an arms race of sorts.

“I pay the salary, I’m eating some of the benefits, my margins are thin, so I really need that loyalty,” Norman said. “I don’t want to invest everything that everybody wants us to invest in the employee, then have them run down the street…for two dollars more an hour.”

There also are generational shifts at play, which may or may not be connected to or exacerbated by COVID. Though no one wants to denigrate young people, employers are noticing streaks of entitlement with those just entering the workforce.

“We're not getting the 18, 19, 20-year-olds to come into the business in the line level and work their way up through,” Norman said. “They're walking in the door and with, again, very little skillset or actual experience and asking to be put in charge of the department. And I'm like, ‘Holy crud.’”

Shifting values also mean that employers may need to readjust what they expect from workers over the long term.

“I don't want to overgeneralize, but you just don’t see the situation in which they want to be with this one employer for 30 years and get that gold watch,” Taylor said. “If you polled the Baby Boomers, their goal was stability. If you poll younger people, it’s flexibility and freedom.”

Retention and the future

Photo courtesy of Madi Taylor

Photo courtesy of Madi TaylorDespite some tensions regarding expectations, employers are working hard to keep current staff in place. After all, just as it costs five times more to get a new customer than to keep one, employers realize their best bet is likely to keep and develop staff – especially when the recruiting situation is so dire.

Munson’s Stein said her organization is spending a “ton of time and effort” on retention. They’re focused on finding ways for employees to feel more genuinely connected with the organization. That includes clearly outlining paths for growth and advancement, new reward and recognition programs, better wellness programs and more.

“Everybody wants to feel this real connection,” Stein said. “We are hearing that loud and clear.”

Employers also say workers aren’t interested in lip service in terms of culture. It’s something that needs to be at the top of the list and relentlessly pursued.

“If you're not committed daily to reinforcing your culture and making sure you’re a good place to work, and letting employees know this is where they should be and that you do care about them, you're in trouble,” Norman said.

Consistently sampling satisfaction is a good way to keep your fingers on the pulse, Hanel said. TentCraft regularly polls employees to obtain a general satisfaction score.

“If it's going down, why? If it's going up, why? You can correlate the things you're doing as an organization. People can leave notes, too,” he said. “It’s just something consistent to measure how your employees feel about your organization.”

While things have been volatile since the pandemic, the consensus is it’s probably too soon to say which trends are here to say.

Wages went up, for example, but there’s now a growing push to back off on that front. Remote work was hot and heavy for a while, but that trend is also regressing to a degree. Anecdotal data also suggests that the worker merry-go-round is starting to slow down. The dust, as it were, still needs to settle.

“I don't think we're seeing what the new norms are with what's going on post-COVID,” McClyde-Blythe said. “These things have been changing over the past couple of years, and it’s been a moving target.”

Employers themselves are also digging in their heels in some regard, which is likely to shift some patterns.

“We’re all reaching a point where we can’t do this anymore to just have a body,” Norman said. “It’s got to be somebody who’s going to (fit and do the job well).”

In the Traverse City region, employers will do the best they can while keeping a somewhat uneasy eye on continued growth in the face of these employment challenges.

“It’s very nerve-wracking decision to just watch more businesses go in…especially when we're already fighting (for employees,)” Norman said. “The number of hotel rooms about to go in this marketplace in the next 24 months is astronomical. Where are you going to get the people? Because all you're going to do is rob Peter to pay Paul.”